McCartney has spent nearly 30 years with “Now and Then” lingering in the back of his mind — amazingly, the time separating its release and “Real Love” is longer than the distance between “Free as a Bird” and “The Long and Winding Road,” the final single the Beatles released in their lifespan — so it should come as no surprise that the finished product hardly sounds haphazard. It’s deliberate and sumptuous, studio wizardry savvily disguising the distance between Lennon’s original tape and McCartney’s new vocal.

One place where there’s an additional word is when McCartney sings “then we will know for sure I will love you” at the close of a verse, an addition that buttresses a melody that dissipated during this moment on the original Lennon demo. That is also the only moment where McCartney’s voice can be distinctly recognized. Throughout “Now and Then,” the voices of the other Beatles are more felt than heard, with McCartney teasing out the song’s inherent emotion with his arrangements, letting his bass, Ringo’s rhythms and George’s chugging strums, not their vocal harmonies, carry the weight.

Robbed of the opportunity to participate in a true final collaboration with his greatest muse, McCartney instead elevates this suggestion of a song into a realized record, one where its elegant, softly psychedelic flow lets Lennon’s longing linger in the subconscious. That regret is articulated clearly in a chorus of “Now and then, I miss you / Now and then, I want you to be there for me / Always to return to me,” words that sharpen John’s original intention with its second newly written clause. It’s a passage where Lennon’s yearning for McCartney intertwines with Paul’s mourning for John, a shared grieving for the partnership that defined both their lives. In that sense, “Now and Then” does provide something of a fitting conclusion to the Beatles’ recorded career — not so much a summation but as a coda that conveys a sense of what the band both achieved and lost.

Tag: John Lennon

#9 Dream

.

TVGuide: Do you think about [John] a lot?

PM: Yes. I dream about him frequently, yeah. He’s such a central character in my life.

TVGuide: Do you have vivid, inspiring dreams of people you love?

PM: I do, really, yeah. There was actually one a couple of years ago where John…there was a song that I was listening to John do in the dream, and when I woke up, I thought, “I don’t know that song.” It was like it was a new song, and I was going to write it with John. I did vaguely remember it and tried to put down a little demo of it, but it didn’t really click. But I still have a little demo. And it was quite cute. I do dream about John quite often. It’s always very nice.

Interview with Paul and TV Guide, May 2001

The Eye Contact

Mark Lewisohn discusses Lennon and McCartney.

Paul and John

There are sweet moments between all of them—Paul playing piano while Ringo does a spontaneous soft-shoe, George and John having an animated conversation about watching the newly formed Fleetwood Mac on a late-night TV show, Ringo slyly laying his hand overtop of Paul’s and Linda’s in the control room as they listen back to the rooftop recordings, which turns into a playfight. But the romantic friendship between Paul and John, fraying yet unbroken, is the band’s, and the film’s, emotional center. It’s constantly flickering in their eyes, in the physical chemistry between them, in the rhythms they fall into that leave everyone else a few inches outside.

Late into the project, Paul notices the theme about coming apart and returning home extending through many of their songs, and John cocks an eyebrow. “It’s like you and me are lovers,” he says drily, then pauses: “We’ll have to camp it up for those.” Often when John goes into his habitual kooky voices and Goon Show-style surreal comedy routines, the oft-abandoned Liverpool kid in him seems to be defending against such moments of intimacy and vulnerability with Paul. That particularly comes up on “Two of Us,” which I’ve always thought of as their love duet; in rehearsals they’ll do it in Scottish brogues, or through goofily grotesque clenched teeth, almost any way but straight.

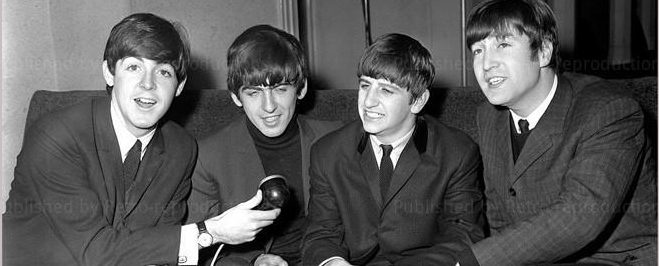

John, Chris, and Tommy

American singers Tommy Roe and Chris Montez were touring the UK with an up and coming British act called the Beatles. According to Tommy: “nobody in the States had ever heard of the Beatles.”

According to Chris, “we got along good together. They seemed like regular guys, just rockers. And they loved music. Paul was real humble and real nice. Ringo and George were real cards. You know, I had a lot of respect for Lennon, and even more now. But he was who he was. Lennon was, I guess, kind of rambunctious.”

The evening of the fight, “somebody in the business threw them a party,” according to Tommy. “ It was in a beautiful house, kind of a country house out in the forest. Everybody was drinking beer and having a good time. And Chris had left the party and was on the bus asleep in his seat. And we all come piling back on. I come on, I sit down next to Chris. And John comes in, all the Beatles come in, and John’s got a beer in his hand and he’s really whacked, you know, just drunk out of his head and pours the beer on Chris’s head… and Chris wakes up, he’s wet with beer, and he goes, ‘Oh man, what’s that?’ He was pissed. And the big scuffle starts, and we start fighting in the aisles and scuffling and, you know, it was kind of ugly.”

Tommy got between them and tried to make the peace. Paul, according to Chris, tried to extend the olive branch. “Paul sat by me and said, ‘Come on, Chris, let’s be friends. I said, ‘Paul, just get away from me, I don’t want nothing to do with you guys. You know, you pissed me off. John? I guess he was a wise guy. But I got the sense that, I shouldn’t say this, that he was jealous of who I was or what I did. I don’t know what his problem was, but I didn’t like it too much.”

Later Tommy says that John demanded his guitar back. ‘Before the fight, John was letting me use his Gibson guitar on the bus to write songs. The next day he said, ‘You can’t use my guitar anymore! That’s it. That’s it! No more. Leave my guitar alone.”

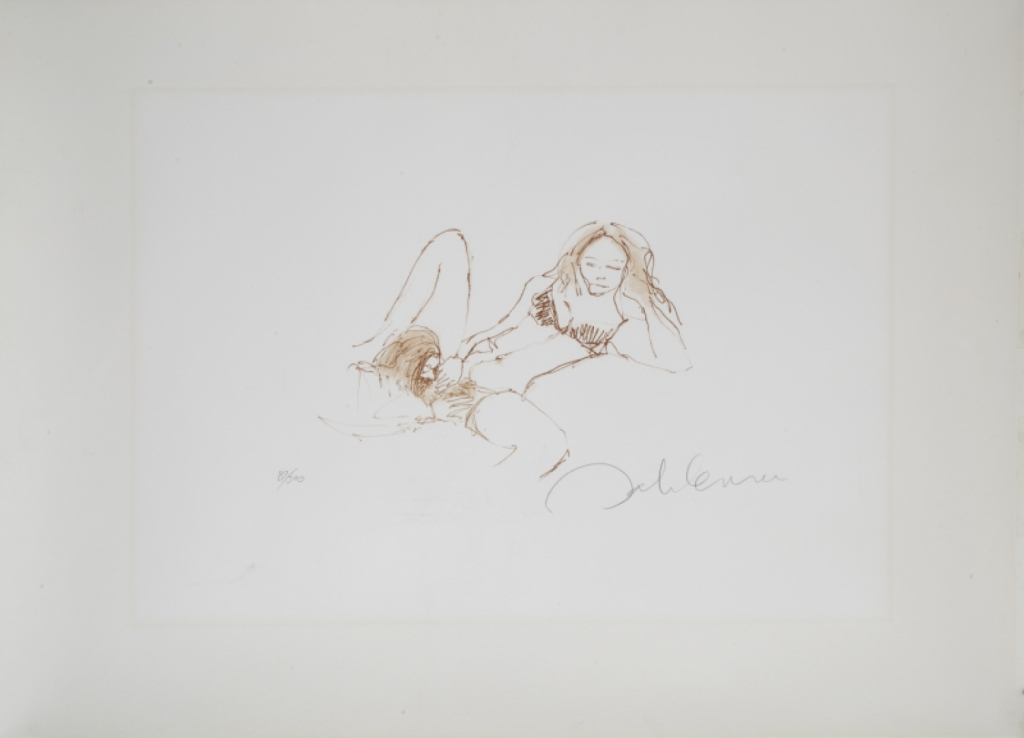

John and Picasso

George Harrison, The Early Years

George Harrison was born in a neighbourhood which, as he once recalled, looked like Coronation Street, but saw out his days in homes which would have been beyond his wildest childhood dreams. A cramped two-up, two-down terraced house in Arnold Grove in Liverpool’s Wavertree area was Harrison’s first home.

The young George lived with his bus driver father, Harold, who had been a seaman for many years, and his mother Louise, who was of Irish descent, and his two brothers, Harry and Peter, and sister, also called Louise.The living room at the front of the house was barely used and the family used to gather in the kitchen for the warmth of the stove and the fire. The Arnold Grove house had an outside toilet, at the back of the yard, like most homes at the time, and, for a short while, a hen house. There was no bathroom, just a zinc bathtub which would be filled from the kettle and pans. As he recalled in the Beatles Anthology: “My earliest recollection is of sitting on a pot at the top of the stairs having a poop– shouting ‘finished’.”

When he was five, the family moved to a new council house at Speke after having spent many years on a waiting list. Like many other children he disliked school–in his case, Dovedale Road Infants –which he remembered smelled of boiled cabbage. Sharing a playground at the same time was John Lennon, although they were unaware of each other due to the two-year age gap.

Harrison has spoken of a happy childhood, during which he would listen to the family radio and hear old dance bands and the familiar voices of Josef Locke and Bing Crosby. But his earliest musical memories were of listening to Hoagy Carmichael songs and One Meatball by Josh White. Elder brother Harry had a portable record player which he would lovingly pack away after each use–and which the rest of the family were barred from touching. But fascinated George and brother Pete would sneak it out and spin discs, listening to artists such as bandleader Glenn Miller, whenever Harry was out.It was through a shared musical interest that he became friendly with Paul McCartney, who would catch the same bus coming home from school. McCartney, then 14 to Harrison’s 13, played the trumpet and they would often talk about their interests, later poring over chord books to learn tunes. The budding guitar hero would sit at the back of class at school, drawing guitars instead of concentrating on lessons.The flourishing friendship between George and Paul saw them head off on a hitch-hiking odyssey to Devon with barely any cash, sleeping on the beach in Paignton. Using a meths burner to cook along the way, the pair survived partly thanks to the goodwill of the people they met on the way and head back through Wales. Paul later moved away from Speke to Allerton, close to Lennon’s home on Menlove Ave, and he swapped his trumpet for the guitar.

Though still at school, Harrison and McCartney would try to get a bit more credibility by sneaking out, ditching their uniforms and hanging out at the nearby art college which Lennon attended.“I remember the first time I gained some respect from John was when I fancied a chick in the art college. She was cute in a Brigitte Bardot sense, blonde, with little pigtails,” Harrison said.“I pulled her and snogged her. Somehow John found out and after that he was a bit more impressed with me.”

Hot Take, Get Back, The Documentary

1. The opening credit “Numerous editorial choices had to be made during the production of these films” and the closing production credits of Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, Olivia Harrison, and Yoko Ono Lennon speak volumes about the editorial choices which were inevitably made–specifically the exclusion of most if not all of the audio/video data regarding Yoko’s involvement in the Beatle Dynamic. (Read Sulpy and Schweighardt’s 1994 book and listen to the Nagra tapes, upon which the book was based.)

2. If the saddest moment in Get Back was Paul’s distress so painfully on display in the beginning of Episode 2, the most horrifying moment was in Episode 3, when John raved about Allen Klein to George (”he knows me as well as you do!”), ignoring Glyn John’s obvious warning about Klein’s transparency and openness (and we all know how that turned out.)

3. The utter awesomeness of the rooftop sessions. Watching Paul give birth to the song Get Back, in real time. The speed by which they write music and perfect their craft. Did I mention the rooftop sessions? This band was born to perform. Period.

4. The hilarity of two young and overly serious constables during the rooftop sessions and their comic attempt to get the most successful band in the world to come to heel, all occuring behind an estatic Paul singing GET BACK, upon whom the irony is not lost that the song started as a protest song against the abuse of power.

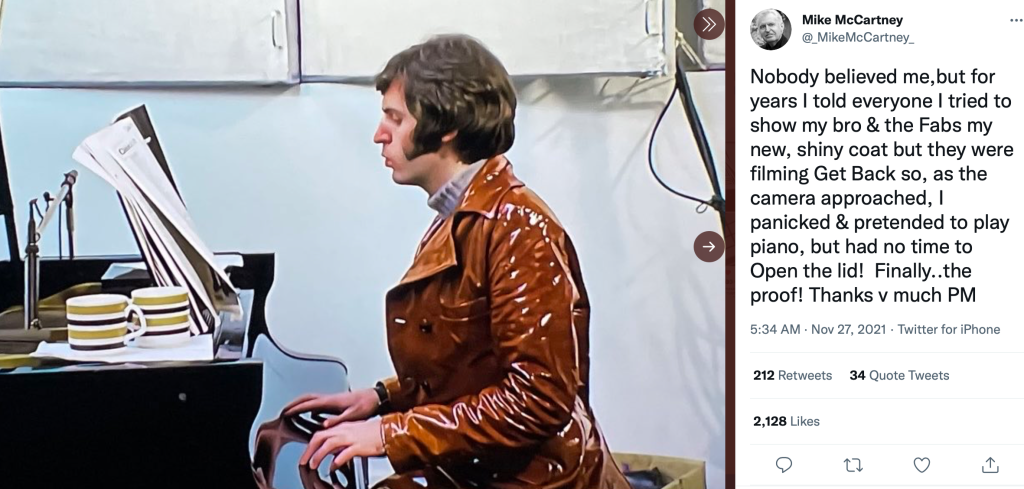

5. And last but not least, the cherry on top (for me): Mike Macca’s inexpected appearance in the film fake-piano playing and engaging in other forms of Mike Macca nuttiness.

Our Characters

The complexity of their characters has been portrayed too simplistically in Paul’s view: Lennon as the tough guy, McCartney as the romantic. “On the surface I think John was more rock n’ roll, but when you scratched that surface the truth of it was that we were all very similar people who showed various sides of ourselves. And it was all to do with how secure your upbringing was. Mine was pretty secure, until I lost my mum. But before that, it was very secure. There were always lots of babies being thrust on me, so when Linda and I finally had a baby it was no worry for me.” He vividly remembers an episode at John and Yoko’s home in New York. “Linda and I went to visit and John and Yoko wouldn’t even let us touch Sean! We said: we’ve had kids, we’re alright, I won’t drop him. I didn’t come from that syndrome where you think they’re like glass when you hold them. I jiggled them and relaxed.”

That incident, and a conversation that followed which explained John’s attitude, brought home to Paul their different backgrounds. “Linda said, as American women do: ‘whenever our family had company, I pretty much had to go to bed.’ Yoko said: ‘when we had company we had to go to bed, too.’ John said: ‘We didn’t even have company.’ And I said: ‘Well, we did and we never had to go to bed. Mind you, it was always Uncle Joe, Auntie Joan, Auntie Gin and other relatives. But we never had to go to bed.’ And I think that meant quite a lot to John.” It underlines, to Paul, the solitariness of John’s youth and the barrier he erected. The healthy partnership and comaraderie that evolved from Paul and John’s competitive streak was only one step away from sibling rivalry. It now transpires that one of John’s earliest hurts conflicted by Paul was McCartney’s solo writing of the music for the Hayley Mills film The Family Way, in 1966. “I was told recently by Yoko that one of the things that hurt John over the years was me going off and doing The Family Way,” Paul says. [Paul had been approached by a third party via George Martin]. “I thought this was a great opportunity. We were all free to do stuff outside The Beatles and we’d each done various little things.” When he mentioned it to John, Paul said, ”he would have had his suit of armour on and said ‘no I don’t mind.’ However, my reasoning would be that at exactly the same time he went off to make a film. He wrote his books. It was in the spirit of all that. But what I didn’t realize was that this was the first time one of us had done it on songs. John would write a book and I was supposed to not be jealous, which I wasn’t. He acted in a film. But I didn’t realize he made a distinction between all those solo things and actually writing music because this was the first time one of us had done it in film scoring.”

McCartney, Yesterday and Today, Ray Coleman

Letter to Harriet and Norman, late 1968

Norman–write to the same address–I haven’t lived there since I was busted by the police–but I have [the mail] picked up. I’ve been living out of a suitcase since I left Weybridge (Cyn’s still there–for three weeks anyway.) Julian is OK. His trust fund–which I set up a few years back is still OK after the divorce, which I can’t wait for,. I’m very happy now–apart from the bad patches–which will all be over soon–and I’d like you to meet Yoko–she’s as intelligent as me (you can take any way!)–most intelligent woman since Leila. She’s also very beautiful–in spite of reports in the press to the contrary–she look like a cross between me and my mother–has the same sense of humour too! When I come I’ll try to bring Julian–if he’s off school–no point in disturbing his schooling as well. Hope you can read this but I didn;t wabt to type it cause it looks official. I think of you all often–and spend hours telling Yoko what a great strange family you/we all are–talk about the Forsyth Saga!

The John Lennon Letters, 2016

A most interesting letter. Highlights: Julian had a trust fund and was not financially abandoned by John, and Yoko looked like a cross between John and his mother Julia. One could have a field day analyzing that tidbit of information.