But no pair illustrates the fluidity of power—and the power of fluidity—better than John and Paul. At its worst, theirs was an alienating, enervating struggle. But at its best, the dynamic was playful and organic.

The tension between Lennon and McCartney was rooted in their distinct styles and personalities. As a boy, the precocious and creative John Lennon always needed, he said, “a little gang of guys who would play various roles in my life, supportive and, you know, subservient.” “I wanted everybody to do what I told them to do,” he said, “to laugh at my jokes and let me be the boss.” He needed both to connect and to dominate. “Though I have yet to encounter a personality as strong and individual as John’s,” said his friend Pete Shotton, “he always had to have a partner.” (John so entwined himself with Pete that he called them “Shennon and Lotton.”)

When John put a band together, he brought his mates in—often simply because they were his mates—but left no doubt about his status. Shotton, for example, didn’t have a particular talent for music and didn’t like it much. When he told Lennon he needed out of the band, John broke Pete’s washboard over his head. It’s not likely we could find a clearer display of power with primates on the savannah.

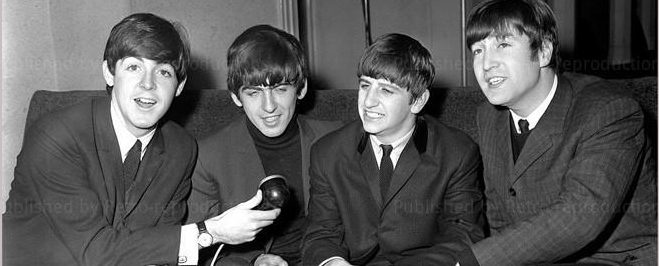

For some time after Paul joined, John stayed out front. Among the band’s many early names were “Johnny and the Moondogs” and “Long John and the Silver Beetles.” When “The Beatles” went to Hamburg, Germany, the contract named John as the payee. In the late 1950s, Paul pitched a journalist on the band; he began his description of the boys with John, “who leads the group … ” But the letter itself—a piece of Paul’s relentless promotion—speaks to his own power style. He was more social, more affable, more outwardly and consistently energetic. Where John oscillated between intense shyness and raw aggression, Paul had a knack for working people that was savvy as it was sweet.

What’s interesting, though, isn’t the question of who ran the show, but the subtlety of strength itself, the many ways power can be exercised between partners.

Consider the moment Paul’s brother Michael cited as an illustration of his “innate sense of diplomacy.” It was in Paris in 1963. The Beatles’ producer George Martin had arranged for them to record “She Loves You” in German. When the band missed their studio appointment, Martin came around to their suite at the George V hotel. They played slapstick and dived under the tables to avoid him.

“Are you coming to do it or not?” Martin said.

“No,” Lennon said. George and Ringo echoed him. Paul said nothing, and they went back to eating.

“Then a bit later,” Michael said, “Paul suddenly turned to John and said, ‘Heh, you know that so and so line, what if we did it this way? John listened to what Paul said, thought a bit, and said, ‘Yeah, that’s it.’ And they headed to the studio.”

How would we chart the lines of authority for this decision? You could say Lennon made the call to refuse the recording session, then reversed himself—the band following him both times. But it was actually Paul who shaped the course the band took. His move to avoid a direct confrontation—to let John stay nominally in control—only underscores his operational strength.

As the band rocketed to success, Lennon would increasingly acquiesce to Paul’s ideas, much as a king in tumultuous times will defer to his counsel. But he never gave up the idea that he could, when he wanted, return straight to his throne.